Such a great book – Guiliano’s book opened up the world of digital history to me. Hard to put down.

There is no question that we should be teaching critical thinking skills – historical thinking concepts – rather than making our students suffer through the intolerable transmission of cold unrelated facts. The question however is not should we be doing this, but how can we do this. As an instructor of new teachers, I struggle with this. How do we teach our students to think critically? How do we apply the rich body of research that has accumulated on historical thinking over the past 25 years?

Here is one clue directly from the research – Tally and Goldenberg (2005) suggest there is a direct link between the development of historical thinking skills in students and the use of digital source material.

I am interested in exploring this link. How can digital history methodology and tools be used to change the way history is taught? How can a new approach actively engage students in inquiry? How do we equip teachers mainly taught through the transmission model to instruct their students in a new way?

Digital History is a relatively new field. The seminal text, Digital History: A Guide to Gathering, Preserving, and Presenting the Past on the Web by Daniel Cohen and Roy Rosenzweig was only written in 2005. Guiliano’s book came out last year. I think both would be great resources for any course on history teaching methodology.

The growing field of digital history offers educators a way to help students develop and hone their historical thinking skills (Hangen, 2015). Digital history requires students to work together becoming active participants in the process of historical research (Guiliano, 2022; Hangen, 2015). Digital history opens up diverse sets of historical source material for the researcher including the digitization of library and archival collections, text visualization tools, interactive maps, and large-scale data analysis tools (Graham; et al., 2022). Digital history also encompasses a variety of tools to share, compare, and publish historical information (Hangen, 2015). As an approach to teaching and studying history, digital history has the potential to engage students and actively involve them in the process of making history (Guiliano, 2022).

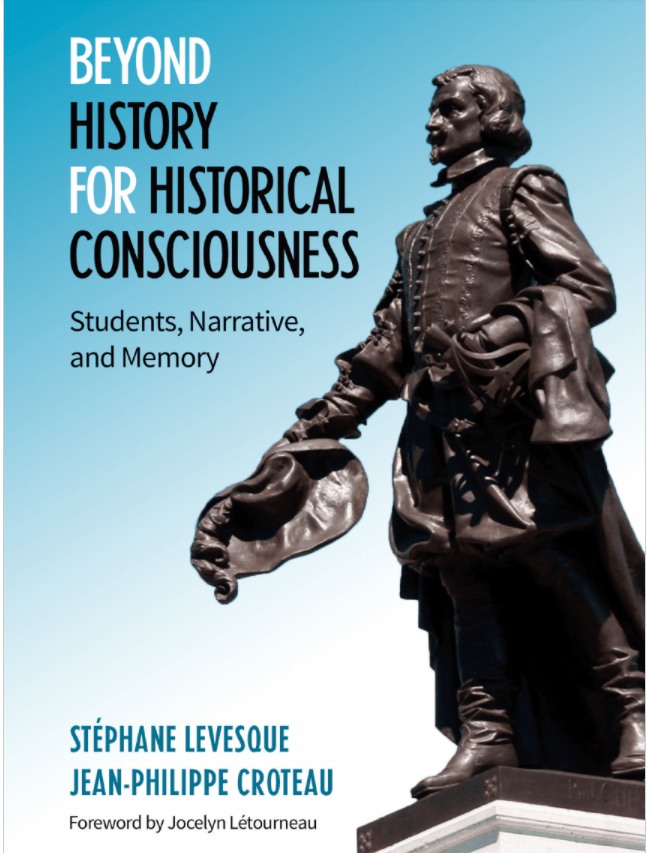

Levesque (2014), reinforces the importance of digital technology, stating that digital methods represent a fundamental break with the past. It is “futile” for students to employ traditional methods of study using the authorized textbook listening to one person’s – the teacher’s – interpretation of history. It is not a question of whether digital technology should be used in the classroom, but how it will be used to further inquiry (p. 44).

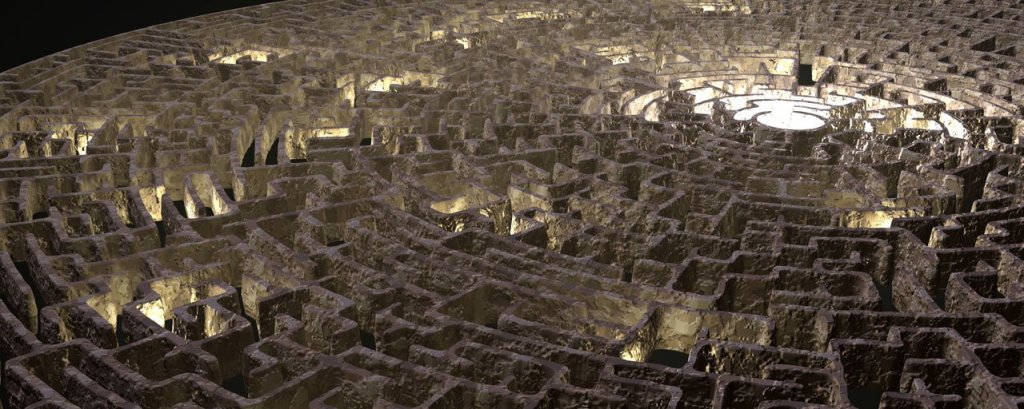

Levesque (2014) writes about the Virtual Historian, a program designed to help high school students navigate their way through the masses of information made available through the internet. Students are provided with a variety of primary source material in order to answer specific historical inquiry questions focusing on various aspects of Canadian history. Indeed, Levesque found that students using the Virtual Historian resource were better able to construct more sophisticated answers to historical queries than students using conventional learning methodologies. Students using the Virtual Historian displayed a greater understanding of the subject matter and a greater propensity to think historically – “present clear arguments supported by appropriate evidence, consider historical significance, and make judgments on the issue” (p. 50).

A key point in this study (2014) – it is not enough to provide students with materials from digital archives and other sources. Developing strategies for analyzing primary sources is a skill that must be taught to students. Unless students learn how to examine source material from a historical thinking perspective, their understanding of historic events will remain unsophisticated. Wineburg (1991) makes the case that students tend to judge material presented to them in the form of historical textbooks as credible and true. Writing in 2020, Barzilaia and Chinn view the problem as much more pronounced. Massive increases in available information online make it all the more challenging for students to assess what sources are reliable. Levesque (2014) contends that more research needs to be conducted to establish a link between digital technology and the development of historical thinking in students. What then is the link between the use of digital sources and the development of the set of skills necessary for students to analyze historical evidence?

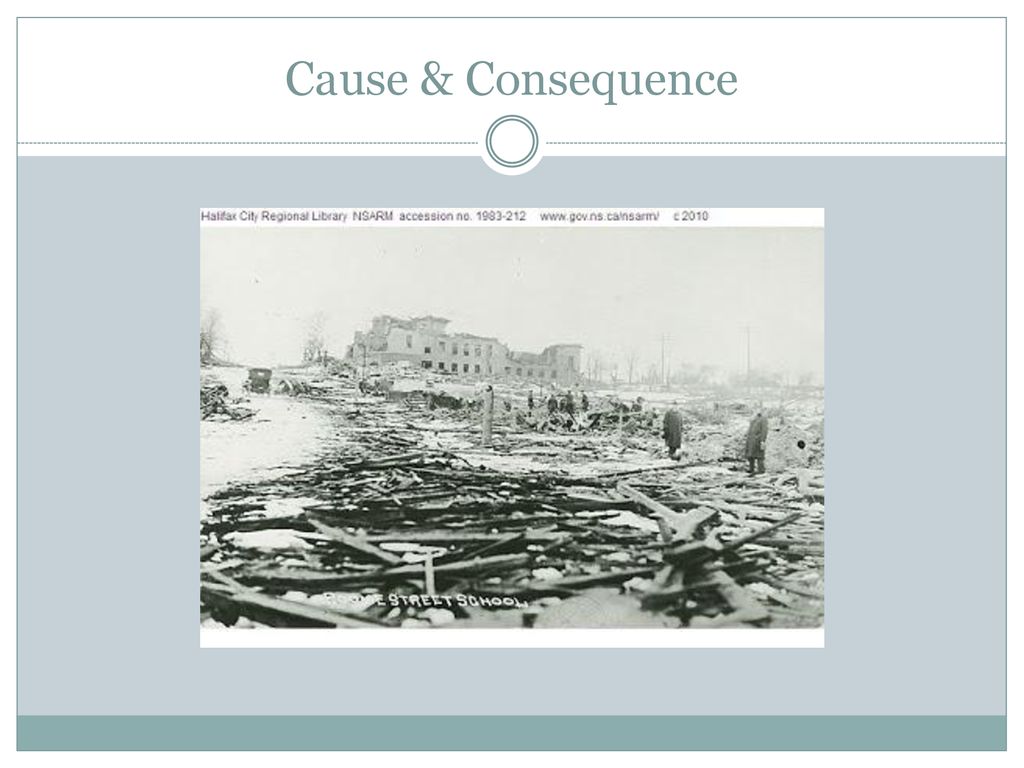

Tally and Goldenberg (2005) suggest there is a direct link between the development of historical thinking skills in students and the use of digital source material. When examining a primary source, they contend, students must follow a series of steps that include a close examination of the documents’ features, an application of their prior knowledge of the historical period they are investigating, and some speculation about the causes and consequences of the event they are studying. Tally and Goldenberg argue that students also need to make personal connections to the events they are examining and use the available evidence to support the speculations they are beginning to make (p. 1). The acquisition of these skills, they conclude, allows for the development of critical thinking skills in history and every other discipline. Their study was conducted using an online historical interpretation activity for students. The central question in their research consisted of an examination of the historical thinking skills students displayed while studying a series of digital images. Student groups of different academic levels and grades were able to make inferences, corroborate information, and use evidence to support their observations and conclusions about the material they were viewing (p. 14). They conclude there is a direct link between the analysis of digital sources and the development of historical thinking skills:

In sum, this pilot investigation of student performance on a digital image analysis task indicates that in classrooms where teachers are using primary sources to actively engage students, students are learning important skills of historical interpretation and document analysis. Scaffolded exercises of this sort described here, coupled with classroom instruction, help students integrate acquisition of historical content knowledge and development of historical thinking skills and immerse students and teachers in building knowledge from documents, in ways that reflect disciplinary perspectives. (p.16)

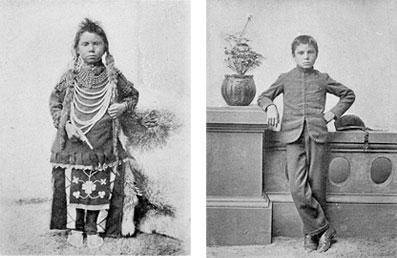

Nygren and Vikström (2013) focus their study on the integration of digital history and historical thinking skills through the use of large digital databases designed for historians. Their theoretical stance focuses on the use of digital archives in the history classroom to assume the historical thinking skills of the professional historian (p. 51). Specifically, they examined students’ ability to sense the difference between the present and the past, the familiar and the strange. This they define as historical empathy – the development of a sense of the lives they are studying through the use of digital archives. In other words, can they sense what Wineburg calls the “jagged edges” of the past (Wineburg, 2010)? Their study was conducted with senior-level high school students over a ten-year period. Students were asked to develop a research question with a supporting hypothesis. The digital database was the source of evidence they were to use in their investigation. In finalizing their work on the lives of people revealed through the database, student work was examined to see if they could perceive the differences between their lives and those of their subjects. Based on their findings, Nygren and Vikström (2013) concluded that using the digital database was a challenge. By the third iteration of the study, the researcher’s introduction to the database and the more limited focus of the study made the use of the digital material more productive (p. 66). Nearly half the students in the final iteration were able to display historical empathy for the people they researched. This, according to Nygren and Vikström, was a clear indication of historical thinking (2013). Digital history methods, they concluded clearly allowed students to delve into authentic historical research, “The very detailed primary sources serve students’ interest in life and death, blood and guts, in a realistic past. Making history meaningful and fascinating is a challenge of history teaching; digital history clearly has the potential to do this” (p. 67).

The authors conclude that the favourable results they recorded were only possible due to the careful scaffolding of their teachers:

Making all students use historical evidence, contextualize and use historical empathy, evidently, takes more than a lesson unit with a digital database. We see the teacher as vital for helping the students understand how to use the databases, but also more importantly, for making the students understand the meaning of this type of history teaching. If the task is incomprehensible, it will appear as meaningless in the eyes of the student. (p. 68)

Different elements of historical thinking can be animated by different digital tools. Carretero et al., (2022) argue that digital historical maps offer students the opportunity to study change over time, one of the key historical thinking concepts as outlined by Seixas & Morton (2013), Wineburg, (2001) and others. Unlike maps in textbooks, digital historical maps can be manipulated, allowing students to see how political borders change over time. Digital maps allow students to create their own content by fashioning elements of the map, changing its scale or focus (Carretero et al., 2022). Digital technology allows access to a wide variety of older maps providing the student with evidence to research some of the probing historical questions posed by Kelly (2014) – who created the map? For what purpose was it created? When was it created? Where was it created? What type of map is it? (Carretero et al., 2022). Digital maps allow for what Kelly defines as the power “to present the past in clear ways, whether in writing or in other media” (2014, p. 23).

Using Old Maps Online to create an overlay – Montreal present day and 1764 – continuity and change?